Remarkable quartz with citrine color from Morocco

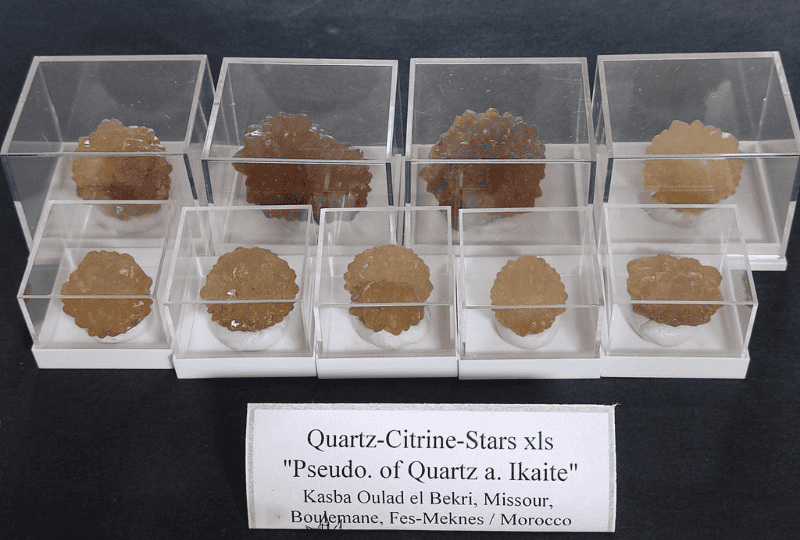

For several years, remarkable shaped quartz crystals have been popping up on the market from Morocco with a distinctive citrine color, ranging from yellow-brown to orangey. Even during the Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines show in June 2025, these pieces were again widely represented by Moroccan vendors under the name “citrine”. Moreover, some of this yellow-brown quartz is offered as“pseudomorphs after ikaite,” particularly the flower- or spherical-shaped aggregates (also known by the names“quartz citrine star” or “glendonite citrine“), but little to no information can be found on these. Reason enough to dive thoroughly into the background of these pieces.

First mentions of Moroccan ‘citrine’

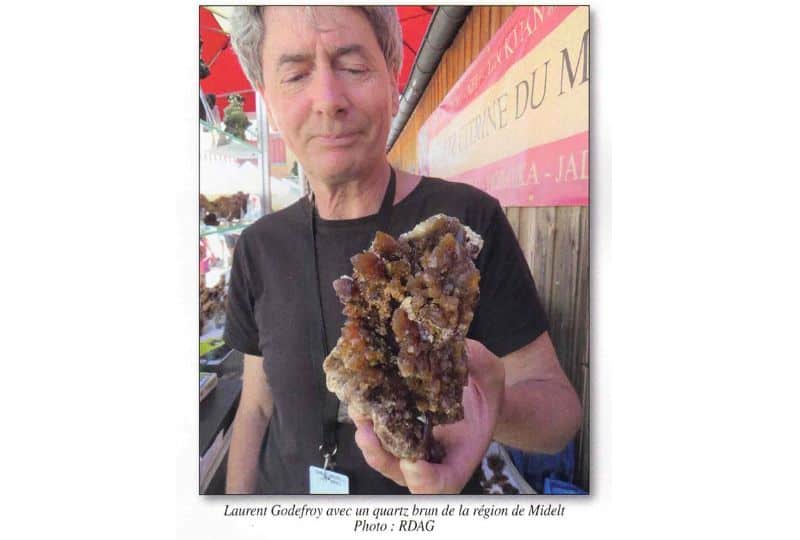

In 2018, Laurent Godefroy, a French collector and mineral dealer who is always alert to Moroccan mineralogical peculiarities, first reported in the journal Le Règne Minéral the discovery of curious quartz crystals with a saturated and strange citrine color from Morocco during the Munich show (Godefroy, 2018)1. At that time, it was only known that these quartzes would come from the Midelt region, the background of the color and the specific growth form was still unknown. For the show in Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines in June 2019, Godefroy managed to collect a large enough batch of specimens to better determine their origin and reconsider their designation (Godefroy, 2019)2.

(Photo: RDAG in Le Règne Minéral, no. 148, 2019)

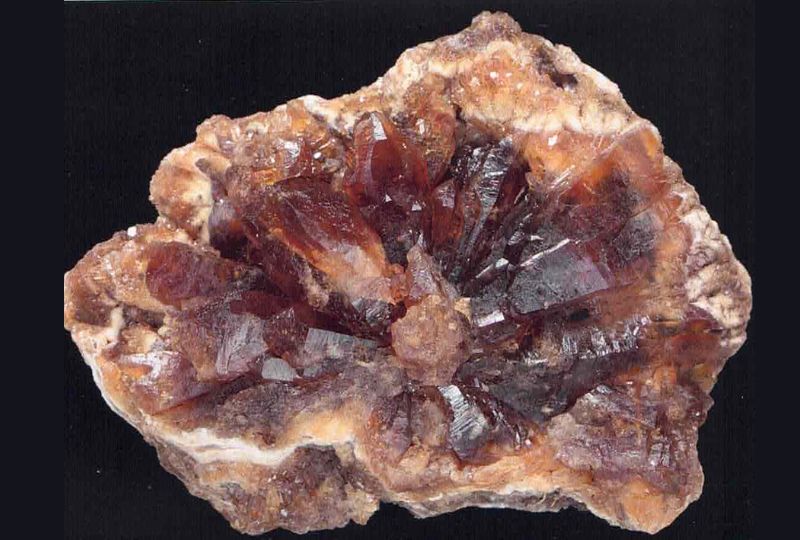

yellow-brown quartz from the Midelt region, Morocco; on the left, a radial-oriented cluster measuring 8.7 x 6 cm and on the right, a crystal measuring 3.7 x 4.2 cm and a radial-oriented cluster around a chalcedony core measuring 3 x 2.6 cm (collection: Laurent Godefroy; photos: L.-D. Bayle in Le Règne Minéral, no. 148, 2019)

Interesting growth forms of quartz

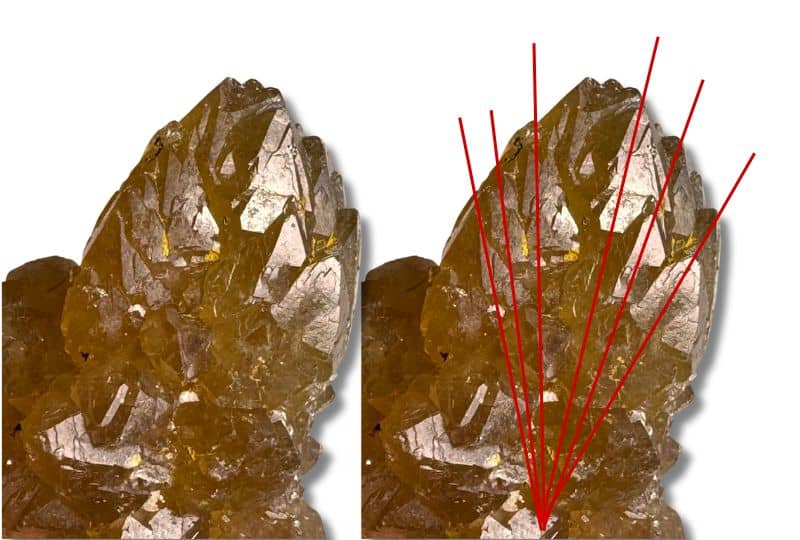

The crystallization form of these quartzes from Morocco is particularly interesting and varied. Several crystals show distinct characteristics of split growth, also known as artichoke quartz. In this process, several crystals grow from one central point in the base, similar to the way the leaves of an artichoke are arranged. In these clusters, the central and side crystals are roughly the oriented from the same point with their longitudinal direction (c-axis), indicating that they formed simultaneously rather than in successive stages.

In addition, there are crystals that end in a point shape composed of slightly curved planes, these are the so-called rhombohedral planes, which together form a kind of small pyramid at the tip(pyramidal quartz). This is different from the more familiar prismatic quartz, where the crystals are more elongated with a distinct prism and a sharp transition to the tip. In this Moroccan material, these prisms are often almost completely absent.

typical piramidal shape with curved edges/faces and no or hardly any prisms visible; in the detail photo on the right, the split growth is also clearly visible (collection and photos: Bianca Schouw, Hidden Gem Minerals)

We also see rather flat growth forms, as known from the amethyst “flowers” from Brazil, and flower- or spherical aggregates and collar-like outgrowths. Such shapes may indicate rapid crystal growth or disruptions in the crystal lattice (Godefroy, 2019).

(donation Stefan van Oers, The Crystal Pocket)

flat growth forms as bases on which grew round flower- or spherical-shaped aggregates of quartz crystals (collection and photos Stefan van Oers, The Crystal Pocket)

The presence of chalcedony in orbicular form as the seed or growth core of the flower-like aggregates, and a matrix that is sometimes clayey or marl-like, indicate a sedimentary origin of these quartzes. They are developed in narrow layers and also contain inclusions of organic material (Godefroy, 2019).

Striking crystal growth, but not pseudomorphs

Some sellers tout these particular quartzes from Morocco as being “pseudomorph after ikaite,” but experts clearly reject this claim. In fact, ikaite is stable only at very low temperatures (below 6°C) in cold, watery environments, such as on the sea floor. No scientific evidence has been found that such conditions ever prevailed at the sites in Morocco. In addition, when heated, ikaite does not turn into quartz, but into glendonite – a variety of calcite (Schultz et al., 2023)3. Cases in which glendonite is subsequently converted to quartz or opal (double pseudomorphosis) are extremely rare and limited to specific sites such as the well-known“opal pineapples” from White Cliffs, Australia.

The confusion seems to stem mainly from the external shape. Both ikaite and glendonite can have complex crystal structures, such as flower-shaped aggregates and curved crystal faces – precisely the shapes also seen in some of these Moroccan quartzes. But as Schultz et al. (2023) emphasize: external resemblance alone is not in itself evidence for pseudomorphic transformation. Moreover, there is no known credible example of glendonite naturally converted to quartz. Moreover, the geological context of the sites in Morocco lacks the conditions for the formation of ikaite or glendonite. Also, no mentions of ikaite or glendonite from Morocco have been found, except on websites of some vendors of these particular quartzes.

two examples of calcite var. glendonite, a pseudomorph after ikaite in which resemblance to some of the Moroccan quartz aggregates can be seen (spherical with curved crystal faces), but also distinctly different termination of the faces on the tip than in the quartz clusters; on the left, an aggregate 6.5 cm wide from the Bol’shaya Balakhnya River, Taimyr Peninsula, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia; on the right, an aggregate 3.5 cm wide from the Olenitsa River, White Sea Coast, Murmansk Oblast, Russia

The Moroccan quartzes show no characteristics of a previous mineral form and lack all traces of a conversion process. Both their shape and composition indicate that they are quartz crystals deposited directly from silica in a sedimentary environment. According to experts, they are simply yellow quartzes of natural origin, with no pseudomorphic antecedents. The story about ikaite seems to be a fabrication of a commercial nature, devised to make the pieces more attractive to buyers. Once such a name appears on labels, it is quickly adopted by other sellers, even though it lacks any scientific substantiation.

Cause of the ‘citrine’ color

The color of these Moroccan quartzes varies widely, and even within a single crystal, shades from yellow-brown and orange to dark brown, almost black, or just white-cream can occur. Analyses of several specimens show that the color is not evenly distributed. Moreover, these quartzes do not exhibit dichroism – a color change when rotated in polarized light, which we do see, for example, in natural citrine with an aluminum background.

using a London dichroscope we see on the left no dichroism in the Moroccan quartz and on the right we do see a clear color change below and above the line between the two perpendicular polarization filters in natural citrine from Congo

Combined with the sedimentary origin of these pieces, this suggests that the color is not created by color centers or radioactivity, but most likely by organic material (Godefroy, 2019). This mainly involves bitumen or related hydrocarbons, which grew with the quartz during its formation. Bitumen is a solid, dark substance that occurs as residue of petroleum. Depending on the amount and distribution of these organic constituents, the intensity of the color varies – from light discoloration to almost opaque dark brown batches.

An important confirmation for the presence of these organics is their behavior under ultraviolet light. Several specimens exhibit a distinct orange-yellow fluorescence under long-wave UV (365 nm). This glow occurs because organic molecules in the inclusions absorb UV light and re-emit it as visible light. Such fluorescence is known in quartz with petroleum or bitumen inclusions, and also occurs in other hydrocarbons such as methane. The exact color of the fluorescence depends on the composition of the organic substance, the wavelength of the UV light as well as any other impurities or structural flaws present in the crystal. There is no fluorescence in natural citrine.

Although an exact identification of the organic compounds requires specialized techniques – such as Raman or UV-Vis spectroscopy – all indications are that the color in these quartzes is mainly due to natural organic inclusions. With that, they fit well within a sedimentary formation environment and are distinctly different from colored quartzes of other origins, such as radiation-influenced citrine, smoky quartz and amethyst.

Probable locality

The yellow-brown quartzes at issue here were first mentioned by Godefroy in the French magazine Le Règne Minéral (2018 and 2019), citing Midelt in Morocco as the site of discovery. However, if you search for quartz from the Midelt region on Mindat.org, you will find mostly the well-known red hematite quartzes of Aouli. No photos of the yellow-brown varieties as we discuss here are available there.

Today, the locality is often given as Oulad Al Bakri , also known by variants as Kasba Oulad el Bekri or Oulad el Bakhi, located in the Fès-Meknès Region. On Mindat, this location falls under the designation: Boulemane Caïdat, Boulemane Cercle, Boulemane Province, Fès-Meknès Region, Morocco. At this location,only two specimens are found on Mindat: pale yellow, flower-like aggregates with a radial-oriented structure. According to the listed owner, this is a find from the area of Boulemane Caïdat, probably from 2021-2022. This material is very similar to what is offered online as“quartz citrine star” or under the misleading name “glendonite citrine,” often with that same provenance statement.

On Mineralienatlas.de, there are no pictures or entries of these quartzes, either at Midelt or Oulad Al Bakri. So the question remains whether these are always the same type of material and the same find site – or if they are multiple similar finds from different regions. At least in appearance, the yellow-brown clusters that have already appeared on the market since 2018/2019 under the name “Midelt” are very similar to recent material from the Fès-Meknès region. Incidentally, these sites are only about 100 kilometers apart. This makes it plausible that confusion or overlap in origin declarations can easily occur, especially when material enters the market through middlemen.

Anyone who knows more about the exact origin of this quartz, or about differences between the sites mentioned, may always come forward – additional information is most welcome.

Conclusion

The yellow-brown to orange-colored quartzes from Morocco offered as citrine and sometimes under names such as “glendonite citrine” or “Quartz citrine star” do not appear to be pseudomorphs after ikaite or glendonite. That explanation is geologically improbable and is rejected by experts. The growth form of the quartzes – such as flower-like aggregates and split growth (artichoke structure) – is well explained within a sedimentary depositional environment. There is no evidence of an earlier mineral form or a process of pseudomorphic transformation.

The color of these quartzes is caused by organic material, probably bitumen, and is not due to iron, aluminum or radioactivity, as is the case with natural citrine or smoky quartz. This is supported by fluorescence under long-wave UV light, which is typical of hydrocarbon compounds.

The exact locality is difficult to determine with certainty, but most of the recent pieces seem to come from the Boulemane region of Fès-Meknès. Midelt, previously mentioned as a site of discovery, is only 100 km away. It is possible that both sites provide similar material or that there is confusion in the trade chain.

In short, these quartzes are naturally formed, but not citrine and not pseudomorph after ikaite. Commercial naming is often misleading and not scientifically based.

This article was created in part through collaboration with Bianca Schouw of Hidden Gem Minerals and Stefan van Oers of The Crystal Pocket. A great example of how sellers together with the knowledge center of Stapel van Stenen contribute to honest and reliable information for the gem and mineral industry.

Do you think this is important as a seller too? Then join the seller community!

To learn more about citrine and how to distinguish it from other yellow quartz, read the article on citrine in the Gem or Scam Library and listen to the podcast episode on citrine (Dutch).

Learn more about quartz growthforms? Take the mini course!

- Godefroy, L. (2018). Quartz à teinte citrine étrange de la région de Midelt, Maroc. Le Règne Minéral, (144), 34. ↩︎

- Godefroy, L. (2019). Quartz de teinte citrine et découvertes minéralogiques récentes au Maroc. Le Règne Minéral, (148), 40-42. ↩︎

- Schultz, B. P., Huggett, J., Ullmann, C. V., Kassens, H., & Kölling, M. (2023). Links between Ikaite Morphology, Recrystallised Ikaite Petrography and Glendonite Pseudomorphs Determined from Polar and Deep-Sea Ikaite. Minerals, 13(7), 841. https://doi.org/10.3390/min13070841 ↩︎

Responses