Fact or fable? – Septarian concretions originate from deceased animals

Septarian is a special stone that attracts attention with its unique appearance. Moreover, an interesting story circulates about the origin of septarian dating back to ancient times. According to the story, septarian concretions (or septaria) were allegedly created from the hardened fluids of deceased animals, hence the nickname “dragon stones.” In this article, I explain how septarian are created and whether the story is fable or fact. By the way, septarian is not a mineral or gemstone as is often thought, but a rock. It consists in most cases of a concretion of clay-ironstone with filled fissures of various minerals. The processes of sedimentation, dehydration and crystallization contribute to septarians unique appearance, with its distinctive pattern of lines or “veins” running through the rock.

Septarian, clay stone with calcite (Beilstein, Landkreis Cochem am Zell, Germany)

Septarian, a special form of a concretion

A concretion is a hard, compact mass formed in sedimentary rock or loose sediment by the precipitation of mineral cement in the space between the loose particles. In the case of a septarian (or septarian concretion), these are clay particles hardening together by a calcareous “cement”. Concretions are often egg-shaped or spherical, although irregular shapes also occur. The word ‘concretion’ is derived from the Latin concretio ‘(act of) compacting, condensing, solidifying, uniting,’ which in turn is compounded from con meaning ‘together’ and crescere meaning ‘to grow.’

Concretions form in sedimentary layers that have already been deposited. They usually form early in the sediment’s depositional history, before the rest of the sediment has hardened into rock. The calcareous cement that binds the clay or sand particles together often makes the concretion harder and more resistant to weathering than the layer the concretion is in. With weathering, therefore, concretions remain and are found by us. Besides septarian concretions of clay, we also know concretions of sandstone, such as the so-called “Moqui Marbles,” and concretions of pyrite.

Left: Pair of ‘Moqui Marbles,’ sandstone concretions with an outer layer of iron oxides (Navajo sandstone formation, Utah, United States)

Right: Pyrite concretion from shale (Dongchuan Cu ore field, Dongchuan District, Kunming, Yunnan, China)

Origin and geological background of septarian

Septarian is thus a sedimentary rock that is formed from muddy sediments deposited on the sea floor or in shallow waters. This mud and clay also contains organic material such as feces, dead animals, plants, shells, and so on. During the putrefaction process, bacteria then play an important role in a chemical reaction (sulfate reduction) and form the carbonate ion (CO32-), among others. Subsequently, calcium ions (Ca2+) from the seawater penetrate the clay. As this creates CaCO3 (= calcite), the clay hardens from the outside toward the center. The calcite acts as a kind of cement for the clay and also fills cracks and crevices. Depending on the composition of the soil, other minerals may also be formed in the process.

It is generally believed that concretions grew incrementally from the inside out. The origin of carbonate-rich septarian is still debated. The currently considered most likely possibility is that drying hardens the outer shell of the concretion, while the matrix of clay on the inside dries out and shrinks, causing cracks. As a result, septarian stones usually exhibit an internal structure of polyhedral blocks (the matrix) separated by mineral-filled cracks (the septa) that taper to the edge of the stone. These cracks then fill with other minerals. The name septa is therefore derived from the Latin word septum, meaning “separation, parting element”. Think of our nasal septum or septum in the heart which are also called septum.

Septarian, two halves of a nodule of clay ironstone with obvious hardened edge and cracked interior, the cracks completely filled with calcite (Oujda, Morocco)

Minerals in septarian

The matrix usually consists of clay-ironstone, while the crack filler is usually calcite. The calcite often contains significant iron and may have inclusions of pyrite and clay minerals. The brown calcite common in septarian may also be colored by organic compounds produced by bacterial decay of organic material in the original sediments. Besides calcite, the cracks can also fill with other minerals, such as aragonite, barite, gypsum, celestine as well as quartz and pyrite.

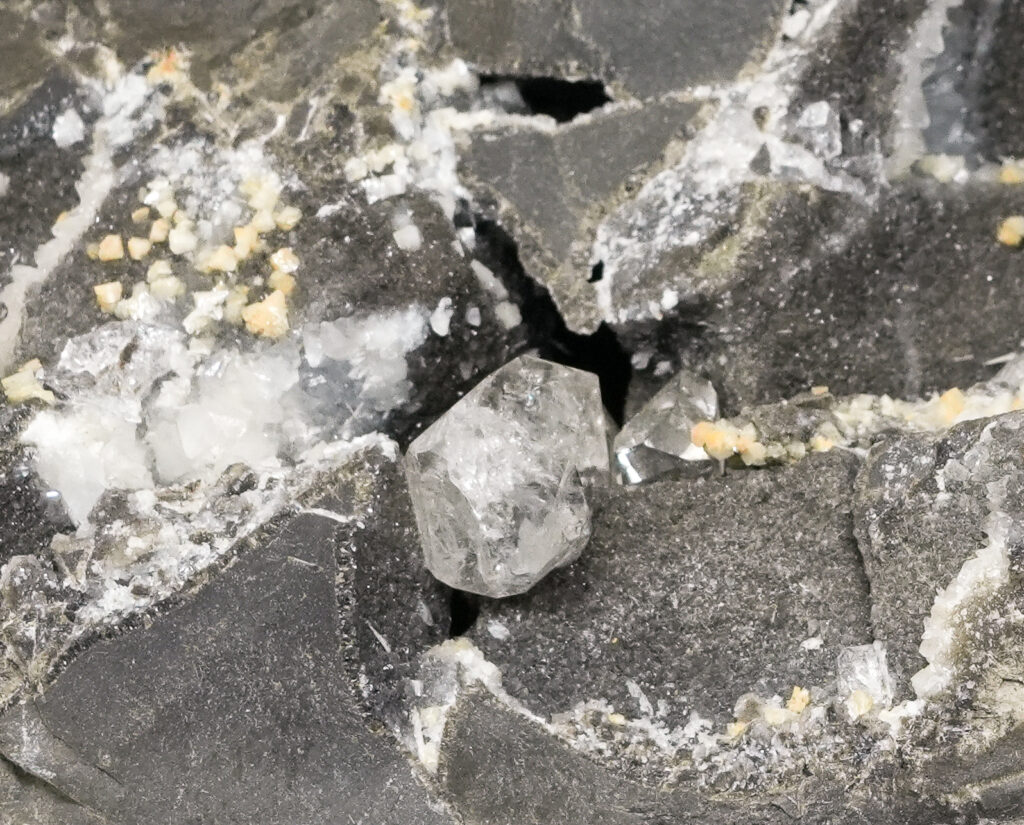

Often the cracks in a septarian are completely filled with a mineral, but frequently a cavity also remains and clear crystals are visible. Beautiful clear quartz crystals are even found in the cavities in septarian. In some cases there is also clear evidence that the initial concretion formed around some kind of organic core, in some septarian nodules we find fossil shells for example.

Septarian, claystone with dark and light calcite, the light calcite has been able to grow visible crystals because the cavities are not completely filled (Muddy Creek, Orderville, Kane Co., Utah, United States)

Left: Septarian, clay stone with calcite and pyrite (Steendorp, Belgium)

Right: Septarian, clay stone with siderite (Arpke clay quarry, Lehrte, Hanover, Germany)

Clear double-terminated crystals of quartz in septarian, so-called “Mirabeau diamonds,” with dolomite (Ribiers, Cote d’Azur, France)

Left: Septarian with barite ‘flower’ on calcite (Warden Point, Isle of Sheppey, Swale, Kent, England)

Right: Septarian, pyrite in yellow clay ironstone (often referred to as ‘limonite’), pyrite exposed by sandblasting (recent find from Pakistan)

Known sites of septarian nodules

Septarian is found worldwide, but some of the best-known deposits are found in areas with large sedimentary deposits, such as Utah (USA), Madagascar and Morocco. But septarian can also be found closer to home, in Germany, Belgium, France and even in the Netherlands, as nodules, chunks or geodes, often near ancient sea beds or former muddy areas.

Left: Tumbled stone of septarian, clay stone with dark and light calcite (Muddy Creek, Orderville, Kane Co., Utah, United States)

Right: Septarian, clay stone with yellow calcite (Ochtrup, Germany)

The Septarian fable?

To come back to the story of body fluids as a source of septarian: so there is some truth to it, but you can’t put it so literally. As you have read above, it is a bit more complicated, although of course it is an exciting story.

The muds and clays from which septarian is formed contain organic material that is converted by bacteria, among other things, creating various minerals. Moreover, the organic compounds produced by bacterial decay can give the minerals a different color. So indirectly, “organic matter” does contribute to the formation of the minerals in septarian, but it is not literally “bodily fluids of dead animals”.

Septarian, clay stone with calcite (Beilstein, Landkreis Cochem am Zell, Germany)

Just beautiful

Septarian thus not only has aesthetic appeal because of their unique patterns and colors, but they also have valuable geological and scientific significance. Because of their genesis, septarian concretions offer insight into sedimentary processes and can help us better understand Earth’s history. But whether you are a geology enthusiast or a collector of gems or minerals, septarian is in any case also simply beautiful to look at.

A modified version of this article (Diutch; Septarie, meer dan gekrompen klei) was published in the journal Conglomeraat of the National Association of Geological Activities in the Netherlands (LVGA), Vol. 1, No. 3, 2024. A PDF of this article can be downloaded here (Dutch)

This article previously appeared in my March 2024 Written in Stone newsletter.

Discover the world of minerals and gemstones every month and sign up for my newsletter! Receive updates on new activities, learn fascinating facts, read the latest analysis and enjoy extensive in-depth stories.

Responses